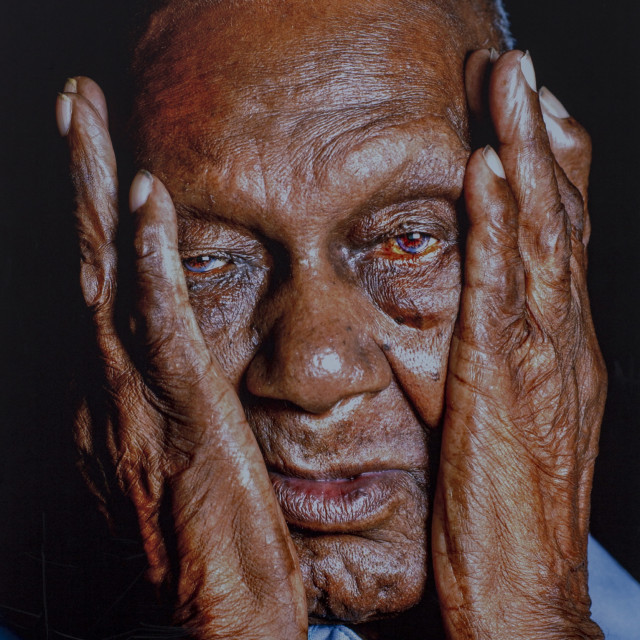

George Blackman

From Barbados, born in 1897. Soldier. Fought in the British West-Indian Regiment in World War I 1914-1919. Photographed in 2002.

From Barbados, born in 1897. Soldier. Fought in the British West-Indian Regiment in World War I 1914-1919. Photographed in 2002.

“Run, Kaiser William, run for your life, boy!” George Blackman hums nostalgically. Rocks in his chair. Closes his eyes. His eyes remain closed throughout the rest of his conversation with the British journalist Simon Rogers. Blackman is partially blind and almost completely deaf.

But he can still express himself. About the year 1914 when he enlisted to fight for his colonial master Great Britain. About the songs they sang to keep their spirits high.

About being called “nigger” by his fellow soldiers, even though they all fought on the same side.

George Blackman was 106 years old when he died three years ago. He was then undoubtedly the eldest survivor of the 15 000 Barbadians who left the sunny Caribbean to fight in the mud of French-Belgian Flanders and the Somme to protect the British king and fatherland during World War I.

In 1914, the then 17-year-old Blackman lies about his age, saying he is 18 in order to fight for Great Britain. He has great enthusiasm and patriotism – he will fight to protect the British Empire.

The voyage to Europe is risky. A large number of Caribbe- an soldiers quite simply die of the cold when their troop transport is ordered to pause at Halifax in Canada. Wearing thin summer clothing, they perish in the unfamiliar and extreme cold. No-one bothers to supply them with the winter uniforms that have been issued to these soldiers.

But conditions will become harsher and the disappoint- ment greater for these soldiers, all so eager to protect the country they think of as their own, all so ready to fight for their king.

This is not to be. The white soldiers are sent into battle, while the colonial troops are given jobs such as loading ammunition, running telephone cables or digging trenches.

The white officers’ attitude is that blacks are not worthy of standing shoulder to shoulder with their own men. But the dramatic losses of soldiers eventually lead to the inescapable need of using the West Indian troops in battle. They are almost left to themselves, and fight with knives they have taken with them from their home- lands.

George Blackman is among those who face hand-to- hand combat. He remembers one special clash in a trench. This is war, face to face, and he is armed only with a bayonet. “You need strong nerves. The enemy makes a move towards you, and you make a move towards him. If he’s dead, he’s dead. If he survives, he survives”, says Blackman.

Blackman survives.

But he will find it harder to survive the conduct of his fellow Allied soldiers.

Blackman is sent to Taranto, Italy, where one of the greatest uprisings will take place. The Caribbean troops again load ammunition, or wash latrines and the other Allied soldiers’ clothes. Their morale is at rock bottom, their pride in serving their country long gone. But there are enormous reactions when the white soldiers are given a rise in pay, and the Caribbean soldiers are not.

A long-suppressed feeling of injustice makes the black men furious. The troops revolt, there are fights among the dissenting Allied forces. Several British officers are killed.

They are punished, these rebels. Many black soldiers are sentenced to long prison terms. But the greatest punish- ment is this: the Allied soldiers march in endless victory parades after having won the War. But not one black man can be seen. “There were no parades for us”, says Blackman. There were no parades for them.

The West Indian troops are instead quickly shipped back to their homelands accompanied only by armed soldiers.

No acknowledgement of their having been a vital resource, a vital protector of the Allies.

Blackman survives the racism, the dangerous war postings, and the discrimination by the Allied military leaders. But his bitterness grows in the years that follow. “When the War was over, we had nothing”, Blackman remembers. He has nothing at all, no clothing, no food, no job, no family. The once proud, enthusiastic Caribbean soldiers are left to their own devices, without recognition, without acknowledgment of their efforts.

George Blackman opens eyes that are almost transparently blue. He has not forgotten the betrayal he felt so strongly about 80 years ago.

"England means nothing to me anymore. Barbadians rule Barbados now.”