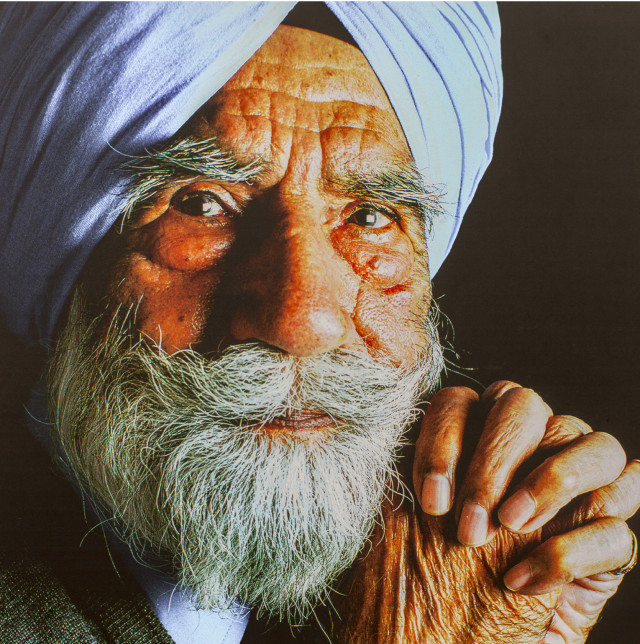

Chanan Dhillon

From India, born in 1923. Civil engineer. Fought in the Allied forces for the colonial power Great Britain 1942-1945. Photographed in 2002.

From India, born in 1923. Civil engineer. Fought in the Allied forces for the colonial power Great Britain 1942-1945. Photographed in 2002.

Tobruq, Libya, 1942

They retreat at midnight. They can see the German troops. A ring of enemies surrounds them, enemies with motor- cycles and powerful weapons. They move farther into the desert, making plans for breaking through their opponents’ lines.

The Indian Chanan Dhillon finds himself among other colonials now fighting for their colonial British masters. They have marched first through what is now Iraq and then continued on through Iran and into North Africa.

They reach El Daba airport, then Marsa al Matruh. A vital battle is being fought in the desert near Tobruq, a harbour city whose excellent facilities for shipping supplies to the front make it an important combat zone.

Some few years earlier a military career was been unthinkable for Dhillon. He grows up in a tiny village in the Ludhiana region of India in the 1930s. Before trudging the seven-kilometre-long road to school, his job is to water the herd of buffalo. At this time little Indian boys go to school to learn to be civil servants for the State, and Dhillon has never thought of becoming a soldier.

But British officers notice Chanan Dhillon’s talent – as an athlete, a hockey player. One British captain named Radcliffe-Smith takes a special interest in him.

He watches Dhillon during a hockey championship played in a hail storm, and loans his coat to the Indian village boy, a very unusual act by a British officer. Six months later, Dhillon is recommended to become an officer. When war breaks out he is a highranking officer in the Indian military establishment. More than four million women and men from the British colonies volunteered for war service during World Wars I and II.

Back to the battle of Tobruq.

When Dhillon’s battalion arrives, the Allied forces are already almost defeated. Surrounded by German troops, they have no choice but to surrender. All prisoners are placed on a ship to Italy. A different kind of battle would occur on this voyage.

60 kilometres off the Italian coast the ship is hit by a torpedo.

The boat sinks in a mere 20 minutes.

Captivity ends, each individual, regardless of nationality, fights for his own life. Survival is now a question of who will manage to grab an Italian life jacket. Out on the stormy sea that is about to swallow the sinking military ship, Dhillon almost dies, he is sure that he will die. But he struggles and wins and is finally picked up out of the water. He is, however, rescued by German sailors who hand him over to an Italian prisoner-of-war camp. The prisoners’ unexpected moments of freedom are gone, but their lives have been saved.

The Australian, British and Indian prisoners in the camp have one common goal: escape. They are engineers and work out a plan together. They dig a tunnel.

And this plan is successful, but only for a few. Chanan Dhillon is among the 40 prisoners who escape, but the turbans he and his Indian countrymen wear show that they are not Italian.

They are again captured and imprisoned.

This could have been the end of Dhillon’s war. But this is 1942 and the Italians are on the point of capitulation. Dhillon and his Indian compatriots are sent to a new prison camp near Frankfurt, Germany, this time. Here he is put in charge of the sector set aside for Indian prisoners. He organizes activities and welfare schemes for the inmates.

Dhillon thinks back. German authorities respect the Geneva Convention, but German soldiers do not.

When some Germans order one of Dhillon’s Indian subordinates to detonate landmines, he refuses:

Dhillon has ordered the soldier to perform nonmilitary duties only. The camp explodes in riots. A German soldier throws a hand grenade and five men, all of them Indian, are killed. Colonel Dhillon insists on inspecting the scene of the riots. The German soldiers are arrested; those in charge of the prison camp are not all-powerful after all.

They are removed and sentenced – a state of emergency in a military context. Dhillon is freed and sent back to India just before the Allies take control.