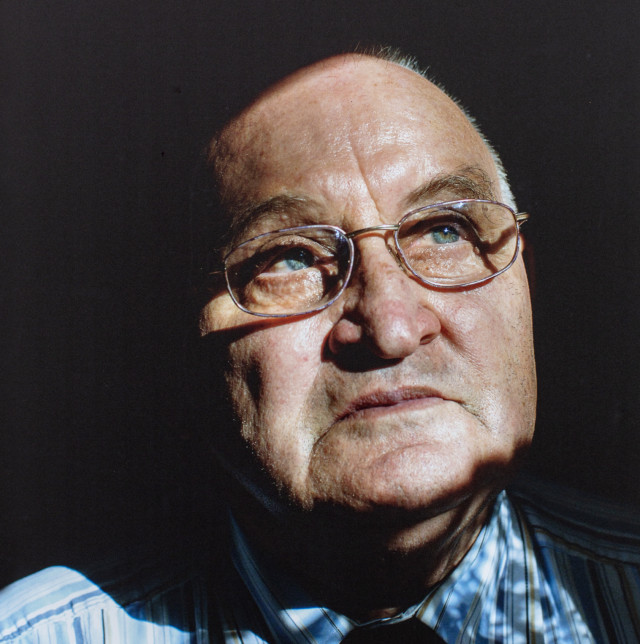

Heinz Küster

German, born in 1927. Soldier in the Wehrmacht and survivor of Russian imprisonment 1944-1945. Photographed in 2006.

German, born in 1927. Soldier in the Wehrmacht and survivor of Russian imprisonment 1944-1945. Photographed in 2006.

It is church bells they hear, the prisoners arriving at the Russian labour camp in Frankfurt/Oder on 12 October 1945.

A sign, they think. A sign that there is hope, that it will be possible to survive. A sign from God about not giving up, as Heinz Küster remembers. In a little German town where everything has been destroyed by bombs and the War, church bells still ring unscathed by the grim surroundings.

Completely exhausted, starved, gaunt after three weeks in a transit hall, the bells light a glow in the German prisoners-of-war. As long as they remain here, they will hear the bells ringing, those three strokes that tell of a life free from imprisonment.

But despite the spark of survival instinct that begins to glow among the soldiers, life is not liveable in the camp.

Their work is clearing away the dead. Carts are shoved over to the hospital barracks where they load dead bodies in piles. Then they push the carts over to one of the many shell holes and empty them. One day there is a movement among the corpses. A man is still alive.

Some prisoners, among them Heinz, jump down onto the pile of bodies, balancing on the dead bodies. The man must be helped, the man must be saved. They are faced by two rifle muzzles from above. Russian soldiers order them to get out of the grave and let the man lie there. There is no alternative. They clamber up out of the mass grave.

The man remains, buried alive.

Heinz’ eyes fill with tears as he says this. 61 years after the War he still has a photographic memory. Gruesome memories are overwhelming.

Everyday life also exists in the camp. There are two alternatives: either you manage to get home or you die. Many prisoners break their own legs or arms by hitting themselves with heavy iron rods in order to be declared unfit for work, and then be freed, Heinz remembers.

But he can’t do that. Cannot even stand the thought.

Besides, then he won’t be able to help his mother with work on the farm. He thinks up a different plan for getting out.

He and two other soldiers each eat a piece of soap. Then they drink as much water as possible. Heinz downs almost six litres. They wait and hope for the best. They hope to be so sick that they no longer are useful to the Russians. They hope to be sent home. But they only get very sick to their stomachs, nothing worse.

The three German boys’ survival trick doesn’t work. Heinz has to think of something else. The next day, on 7 December, he decides to starve himself out of the camp. He refuses to eat or drink. After three days he

is so weak that he cannot walk alone. After ten days he ends up in the infirmary.

On December 26 Heinz is allowed to write a letter. It is the first letter he has written since being sent out to fight. And it is obvious to him that it will be his last. Heinz knows that he is dying; he believes that he will die. He writes to his mother. He writes that he will not survive. He tells her to say goodbye to his favourite horse, Fanny, there on

the farm.

But events will turn out differently than young Heinz thinks and believes. The Russian doctor, a woman, at the camp feels sorry for him, this boy she calls “Little Küster”.

He is not to give up.

She convinces her superiors. With his poor health this boy is worthless to the Russians. On 27 December he is set free. He has succeeded at the very last minute.

Heinz cries, shouts, laughs; he needs help from two other soldiers just to stand upright. He weighs 36 kilos. But he is going home.

His only problem is that letter. That letter waiting to be sent, that the Russians are going to read and where he dripped tears on the page as he wrote that his starvation was selfinflicted.

That is equal to an attempt at escaping. It will result in Heinz’ being thrown into the black hole and in the other soldiers’ being punished.

But Heinz is lucky again. He manages to get that letter lying in the outbag and have it burned. At three o’clock in the afternoon on 28 December 1945, he stumbles out of the main gate, out into freedom, back home to Fanny and to his mother there on the farm.

More than 60 years later Heinz has not been able to forget the bellringing that lit a beam of hope in him and the other prisoners in those dark Christmas days of 1945. He has not stopped wondering which church the sound came from. But luck will be with him once again.

On 30 October 2005, at exactly 9.20 AM, a man living next to St George’s Church in Frankfurt/Oder holds a telephone out of his window. Heinz Küster listens on in the other end.

It is the same sound, and it gives him the same indescribable feeling 60 years later: “It was a very special moment in my life. After six decades the sound of those church bells rang just as divinely as it did then.”