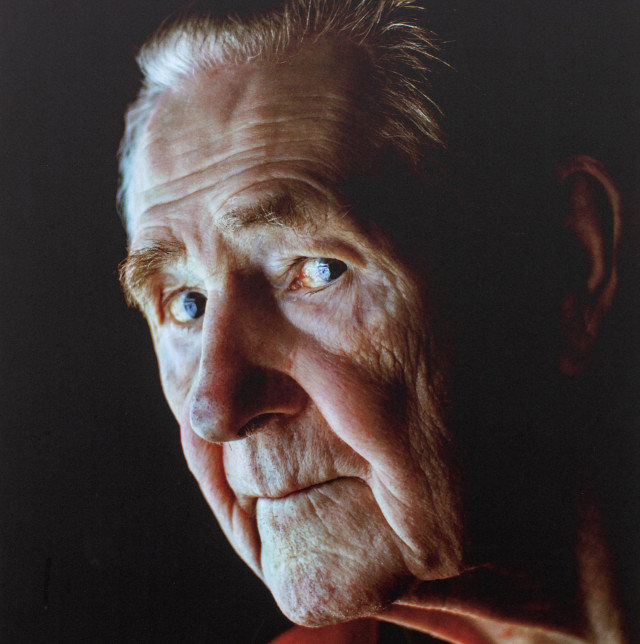

Jarle Saursaunet

Norwegian, born in 1923. Frontline soldier in German service 1943-1945, German identity 1945-1949. Photographed in 2006.

Norwegian, born in 1923. Frontline soldier in German service 1943-1945, German identity 1945-1949. Photographed in 2006.

A little step backwards. Another one. A helping hand from the German next to him. A few centimetres extra room. One more step.

He is finally all the way back. 22-year-old Jarle Saursaunet from Beitstad in North- Trøndelag County stands on a lorry bed. He has been captured by the Russians after the final clashes in Berlin in May 1945. The only thing he can think of is getting off that lorry. Off, and then far away. Otherwise he will die. He does not want to die.

Helped by the others on the lorry bed, he manages to throw himself backwards under speed. He lands on his back, knocks his breath out. Has he been spotted by the Russian guards? For a split second he thinks he can see a head move. He runs across the street into a park. Dead bodies lie everywhere. One of these is going to save the Norwegian frontline soldier.

Two years earlier, in May 1943, Jarle Saursaunet is standing on a quay in Oslo. Along with 20 others young Norwegians from Beitstad he will board a German ship,

the 14 000-ton “Monte Rosa”.

He wants to serve Hitler. Jarle will fight because he hates communism, bolshevism, the Jews. He has learned his Arian lesson by heart; he has already worked for the Norwegian Nazi movement for a few years. About 15 000 Norwegians volunteered for service

in the Waffen SS during World War II, more than 6 000 of them fought in various divisions as Hitler’s special forces.

Jarle is among the 700 Norwegians in Regiment Norge and, after a period as a recruit in Germany, he is stationed with Hitler’s tank corps in Croatia.

He works as a messenger, a guard, an odd-jobs man. Later he is specially trained to work with various vehicles, from motorcycles to Opel’s heavy-duty Klöckner lorries used to haul cannons.

This training proves useful in 1944 when he is sent to Narva on the eastern front, the border between Russia and Estonia. His last duty as an elite soldier in Hitler’s army is to defend Berlin. The soviet attack on the city begins on 21 April; the Germans are forced to capitulate on 7 May. Jarle ends up in a bombed-out apartment building where he is captured by soviet troops and then commanded to climb onto the lorry bed.

Now he looks around the park, looks at the dead bodies. He knows he has to get rid of his uniform showing that he is a Norwegian SS soldier. He throws it into a ditch.

He works fast. Strips the uniform off a soldier, takes his crucial papers, his pay-book. The pants are a bit too short, but will pass muster. He manages to get the ID-disk from the dead body – the young soldier’s neck is nearly blown off. Must have been hit by a shell fragment, Jarle thinks. From that day in May, his name is no longer Jarle Saursaunet, but Walther Schönen, as it will be for the next four years.

He studies his new identity, studies the papers he got there in the park. Walther Schönen, a Wehrmacht soldier born in 1924. This is two years younger than his real age: that’s no problem. His German is fluent. He gets some civilian clothing from an obliging nearby family. Now there’s nothing left to expose him. Walther feels happy. Lucky.

He starts his new German life in the small town of Vachdorf just outside Berlin. He is set to work on a farm, later in some forests.

But Jarle still exists in Walther’s life. The young Norwegian discloses his story to a few people whom he has dared to trust. Some of them will prove very important in Walther’s future. Among them is Dr Behr, a former civil engineer, then a soldier, wounded at Stalingrad.

His present job is to register German soldiers and get them back into working life. While drinking a beer, and very hesitantly, Walther explains the choices he has made. Dr Behr nods slowly. Takes out a pen and paper. Writes down the address of a place far to the north.

This is how a mother and father back home in Beitstad learn that their son has survived the War. Parcels and letters from his Norwegian family give secret encourage- ment to the conviction that home is somewhere else.

But Walther’s uncertainty is still too strong, and he doesn’t dare do anything but forget his past for the time being.

A year passes; it is now the summer of 1946. Conditions begin to be harsher in the little east-German town of Vachdorf. Walther senses the changes. The communists run the town, and candid conversations are held only among very trusted friends. One dictatorship is about to be exchanged for another.

DDR, the German Democratic Republic, appears. Life in Vachdorf slowly becomes shackled. Early in 1948 Walther makes a decision. He is persuaded by a friend to flee to the BDR, the German Federal Republic. They decide to leave on Easter Tuesday.

First a train trip, then a short hike, an arranged meeting at an inn and finally a last, 30-metre, nerveracking crawl gets the two East Germans over the border.

It is now that Ella Pilz, one of the circle and a teacher in West Germany, becomes an important link in Walther Schönen’s future. She manages to get him a job in the coal mines in the little town of Herten. Here he builds himself another life. More people become acquainted with his story, but here in the West his real identity is no danger to him, freedom reigns, and almost three years have passed since the War ended.

Some talk about joining the Foreign Legion leads to Walther’s being sent his necessary papers from Norway. But his birth certificate does not arrive alone. “Welcome home” is written on a letter, sent by Norway’s Foreign Office. The envelope contains food coupons and tickets back home.

Walther makes a decision that he has been unsure of, but that has lingered in his mind the whole time. In October 1949 he gets on a train bound for the country in the far north. This will be Walther Schönen’s last journey.

Jarle Sausaunet returns to Norway. More than six years have passed since he boarded the German troop trans- port, the “Monte Rosa”.

A year later and now firmly reestablished at home in North Trøndelag County, Jarle is sentenced to hard labour for one and a half years for war crimes. He serves three months in Ilebu Prison, the former Grini concentration camp, but is pardoned after three months.