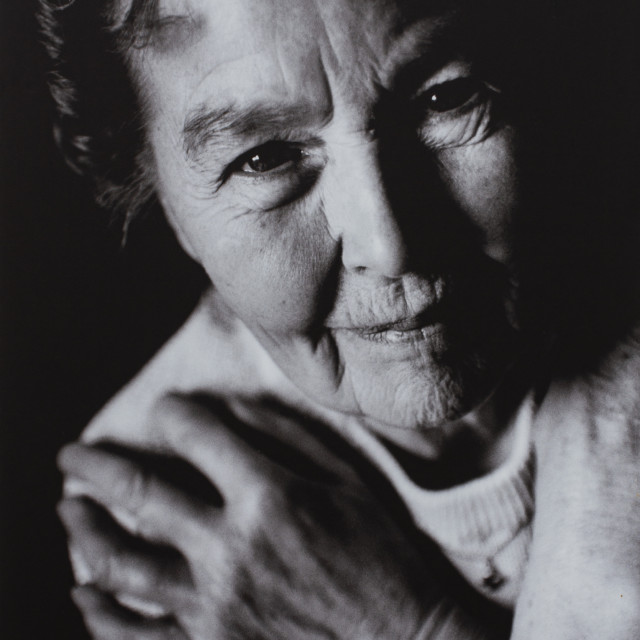

Magnhild Bråthen

Norwegian, born in 1924. Survivor of the concentration camps Grini and Ravensbrück 1943-1945. Fotografert 1995.

Norwegian, born in 1924. Survivor of the concentration camps Grini and Ravensbrück 1943-1945. Fotografert 1995.

It is March 1943. Magnhild Pedersen, as her name was then, will soon celebrate her 19th birthday. After her mother died six years earlier, Magnhild has had full responsibility for the animals on the family’s farm in Østfold County.

She likes the work, likes working with animals. Life on the farm with her father and two brothers continues as before, although the country is at war.

The farm has two lodgers, a father and son, who will lead to trouble for the Pedersen family. They belong to a resistance cell. A violent explosion and a dead game bird near Pedersen’s farm interests the Germans.

They are sure there are weapons hidden on the farm. They show up in the farmyard and begin a thorough earch of the farm. They find nothing, not even those lodgers who have managed to escape to Sweden.

But the Germans do not leave emptyhanded. Magnhild, her brother and her father are arrested.

Wearing a light summer dress, Magnhild is forced to leave the farm and the animals. She, who has never left her own district,

is now taken to the prison in Moss for harsh questioning.

Hour after hour, day after day. The same questions, the same threats, even though Magnhild has nothing to confess. But the Germans don’t need a reason, they need workers.

Both she and her father are sent to Grini, outside Oslo. Her father is released after a few months, however, while Magnhild is put on the ship “Monte Rosa” and sent to the women’s camp Ravensbrück in Germany. For the next two years she will only be identified by number – prisoner Nr. 24 141, address barracks no. 7. A crossmark on the back of her striped dress and a red chevron identify her as a political prisoner.

Ravensbrück, a few miles from Berlin, was a women’s camp whose inmates were uses as slave labourers.

Of the roughly 132 000 women who were held in the camp during the War, it is estimated that about 90 000 perished. Magnhild was one of 103 Norwegian women sent there.

These women become an important resource for German industry. They work in nearby factories or are set to sew clothing and uniforms. Magnhild shovels sand into carts, and then pulls the carts away, very hard labour. She also draws the enormous road roller used to level the roads. Ash from the crematorium is mixed with the sand to make it lighter.

Conditions in the camp are terrible. Scant rations of bread, a little soup, a little coffee. Masses of lice, fleas, scratching oneself bloody. Two prisoners in each bunk and crowds of cockroaches on all the ceilings. An infirmary where dead bodies are piled like firewood along the walls. She was once among those bodies in the infirmary. She and two other women lay in the same bed, Magnhild alive in the middle, the two others lying dead. But Magnhild got up, out, back to work.

But despite the wretchedness Magnhild also has good memories. Intense and strong loyalty existed among the prisoners with friendship that kept up their feelings of human dignity, feelings that the Nazi strived to wipe out. Magnhild describes some of her coprisoners as sisters, some even as mothers.

They take care of the young farm girl, who once cared for her farm animals. This care together with their learning to become invisible, to do what they are told no matter how stupid it seems, may be what keeps them alive and able to survive Ravensbrück.

One day in April 1945, some white busses roll up to the gate outside the camp. The Danish prisoners are called out by the commander. Then the Norwegians.

What they hear seems unreal. Magnhild is told to take a bath. She is given good, clean stockings and shoes. She wears a dress once again, but this time it’s of red silk. The Swedish Red Cross waits outside the gate. They call out “Good morning” in Swedish, Magnhild remembers. The most wonderful words.

The War is over. Two gruesome years in Magnhild Bråthen’s life, stolen by Germans soldiers for no real reason, are over. They sing the Swedish national anthem in the bus going home.